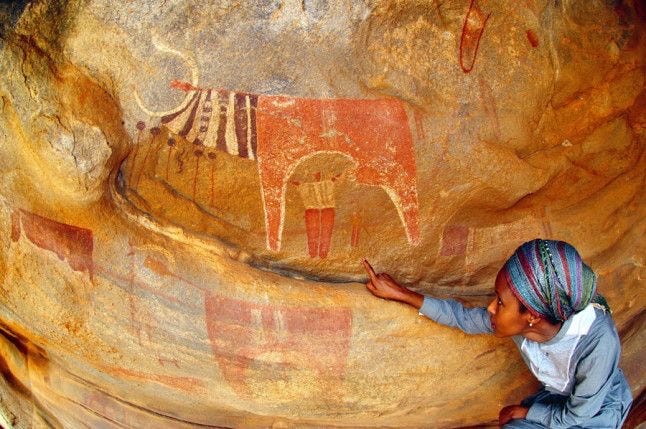

In Western education, the superiority of ‘history’ over ‘pre-history’ has been emphasized due to the tangibility of the written record with which our more linear focused minds can interact with. This, alongside the deemed importance of understanding civilization, that many also feel they can relate to, and feel more safe within, than a more nomadic animistic way of living.

This dismisses 98.5% of our human story, because it’s harder to pin down or grasp the meanings of the symbols and images, oral histories and myth, and consider them as ‘factual’ evidence because they are seen as too open to interpretation.

As Tyson Yunkaporta says ‘if you want to understand the symbols from the past, why don’t you ask the people who still use them instead of listening to archeologists arguing over their meaning.’

Tyson Yunkaporta belongs to the Apalech clan in Australia, and communicates the deep intelligence of cultural knowledge, and how it’s transferred and shared over time.

To many western minds, oral histories are thought to be unreliable sources, even though this has been the main form of passing down the knowledge of the past, since the dawn of time.

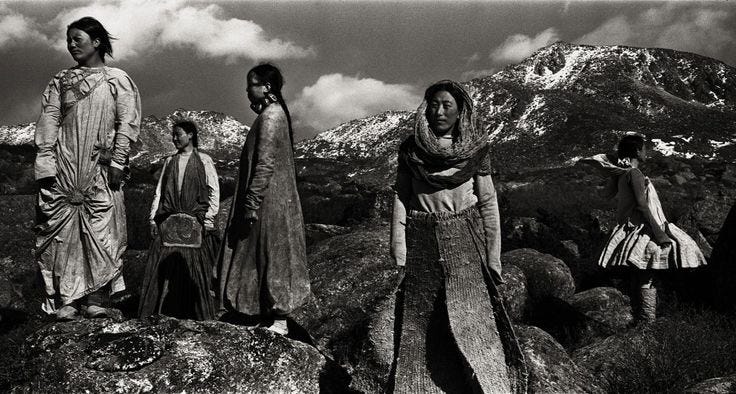

For most, if not all, indigenous cultures, oral history is the primary form of passing down the lessons, memories and wisdom of the past. The stories and songs that are passed down are deemed reliable because they’ve been held within this sacred lineage, with process and protocols in place to protect what is shared. Certain stories are only shared to those who are ready, and in that way less distortions to stories take place because the correct rites of passages and initiations have taken place to receive, hold, honor and share the stories.

‘A person “of high degree” in traditional knowledge may find a song in a dream if they are profoundly connected to land, lore, spirit and community. But that sound must then be taken up by the people and modified gradually through many iterations before it becomes part of the culture. Besides, that song can only be found through a ritual process developed over millennia by that community. The song itself is not as important as the communal knowledge process that produces it.

Most lasting cultural innovations occur through the demotic— the practices and forms that evolve through the daily lives and interactions of people and place in an organic sequence of adaptation. When these processes are unimpeded by the arbitrary controls and designs of elevated individuals, they emerge in ways that mirror the patterns of creation.’

— Tyson Yunkaporta, Sand Talk

Storytellers and wisdom keepers are revered and respected for this process because of its importance, but they are also embedded into the lore of the land and culture, to protect from inflated egos who could impede this process. Of course, each teller may shift the story slightly to also suit the time that they’re in but this means that history is alive, relevant and meaningful, as we continue to live the myths and the histories in new and different ways.

What is fundamental to this deep and rich understanding is also the context and place where the stories sprung from. Many ancestral stories shared make sense and are relevant to their environment. So what happens when they are uprooted and shared out of context? They start to lose some of their meaning and become floating stories in our minds, without the pathways to dig deeper into the wisdom of them.

In our Westernised modern world, we’ve lost touch with a lot of the complexity of myth and story, that holds the key to important lessons and guidance in our lives.

What happens when indigenous ancestral stories become adopted to a ‘detached from place’, and disoriented culture? When religious doctrine imposes itself to sanitize and moralize stories away from their original nuance and depth? When we overly emphasize safety and light and love for children (and adults) so remove the darker and more dangerous aspects of story that prepare for those aspects in life.

What happens when war-mongering cultures supersede and colonize more earth-based and peaceful cultures? The stories get adapted and forced into submission.

In this Living Myth series, we’ll start to explore some of the stories that have changed and adapted over time to track the changes in history, and perhaps within ourselves also.

Also, excitedly we will soon open up our Living The Story membership and community to invite you in to monthly calls to share this together. More on this to come soon!

“A story must be judged according to whether it makes sense. And ‘making sense’ must be here understood in its most direct meaning: to make sense is to enliven the senses. A story that makes sense is one that stirs the senses from their slumber, one that opens the eyes and the ears to their real surroundings, tuning the tongue to that actual tastes in the air and sensing chills of recognition along the surface of the skin. To make sense is to release the body from the constraints imposed by outworn ways of speaking, and hence to renew and rejuvenate one’s felt awareness of the world. It is to make the senses wake up to where they are.”

— David Abram, Spell Of The Sensuous