Indigenous Roots of Christmas 🎄 Part 1

Ancient European Traditions & the Female Shamanic Deer Mother

This week, we’re beginning a deep dive into the shamanic, animistic and deep feminine, or simply indigenous roots of Christmas traditions.

This can also be described as pagan Christmas traditions. However, this can get confused within the pagan revival where a lot of traditions and information has been interpreted, guessed, or simply made up.

There is no definitive answer to what is exactly pagan, or pagan influenced, with each Christmas tradition, but there are many clues from across different Ancient European traditions that we can explore.

One popular theory is the psychedelic origin theory of Christmas traditions.

Beginning with the Sámi, indigenous to the region of Sápma (known also as Lapland), which today encompasses Northern Finland, Norway, Sweden and the Kola Peninsula in Russia.

The Sámi are traditional reindeer herders with shamanic tradition of consuming the red-and-white Amanita Muscaria 🍄 a psychedelic mushroom, that grows primarily around pine trees.

‘They also drank the urine of their reindeer who consume the mushroom as part of their diet and metabolize its toxins without harm, excreting a fluid still full of psychoactive compounds but free from toxins.’1

One of the effects of Amanita Muscaria is the sensation of flight which may have led to the vision of ‘Santa’ flying with reindeer.

The mushrooms were also typically hung to dry on pine trees, and later collected as gifts.

“So, why do people bring Pine trees into their houses at the Winter Solstice, placing brightly colored (Red and White) packages under their boughs, as gifts to show their love for each other and as representations of the love of God and the gift of his Sons life? It is because, underneath the Pine bough is the exact location where one would find this ‘Most Sacred’ Substance, the Amanita muscaria, in the wild.”

–James Arthur, “Mushrooms and Mankind”

After the shaman collects the mushrooms, they may return to their yurt by sleigh pulled by reindeer.

‘In winter, snow drifts can cover the yurt’s main entrance, so the shaman enters through the smoke hole at the top (Santa coming down the chimney) to deliver his gifts to appreciative clan members.

…

To further dry the mushrooms, the clan members string them up around the fire place. In the morning, they awaken to a ritual feast of dried magic mushrooms (Christmas gifts placed in stockings over the fireplace). Once they ingest the mushrooms, the celebrants leave the physical plane and are transported to the mystical realms of the Cosmic Tree, guided by spirits that live within the mushrooms (Santa’s helpers, elves that live in the North Pole).’2

It appears that the connection between Christmas and the Amanita Muscaria was still represented in the 1900s, perhaps proof of a through-line of these traditions.

The traditional costume of Sàmi women and men gathering the mushrooms was red and white, again perhaps pointing to how these colors became associated with Father Christmas, and Christmas in general.

Our contemporary image of Santa Claus as a rotund, jolly white-bearded fellow in a red suit (or robe) with white fir trim is a modern version of the archetypal Siberian mushroom shaman. In fact, even today some Siberian male shaman and female mushroom gatherers still dress in ceremonial red and white trimmed jackets when they go to gather the sacred mushrooms.3

What about the Deep Feminine roots of these traditions?

Historically, it’s understood that there were more women than men in a shamanic role in Siberia (where the word shaman comes from).

‘Woman is by nature a shaman’

— Chukchee Siberian Proverb

A vast number of shamanic, ritually significant and high status burials in Europe are female.

The shamanic role also transcends all gender, and human confines, to channel a full spectrum of different spirits for healing or divination. Furthermore, an indicator of shamanism is an ability to shapeshift into various animal forms and channel their characteristics.

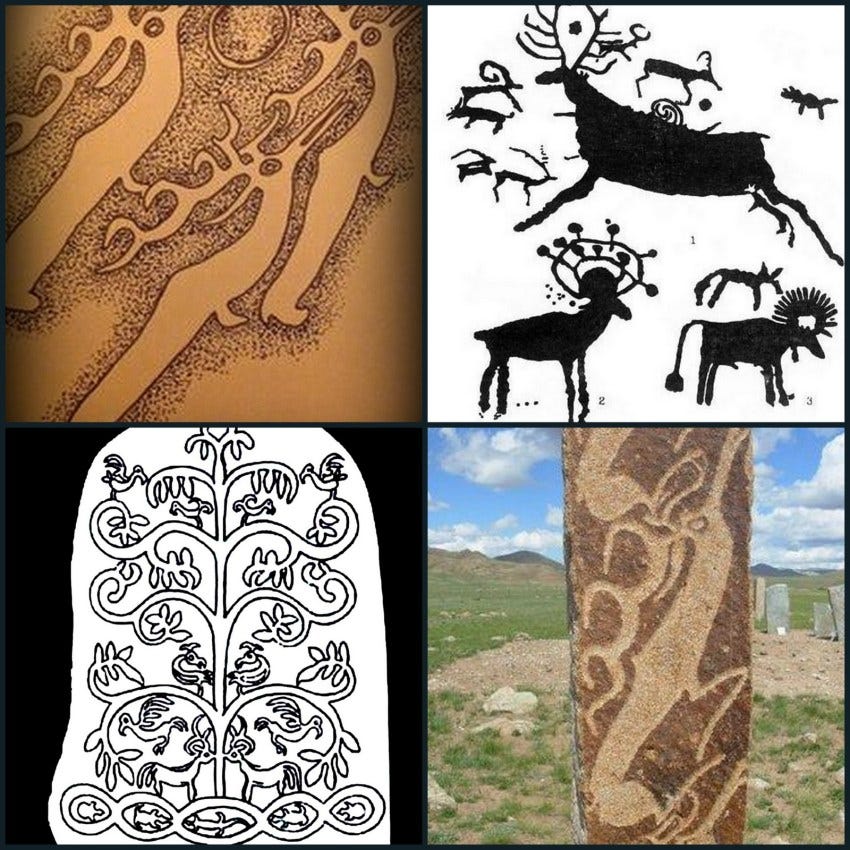

According to Evenkian mythology, the giant Elk-Female, Bugady-Eninteen, was the mother of the animals and hostess of the forest. Her image was portrayed on the sacral Bugady rocks (Evenkia District, Russia), dating from the Neolithic.4

‘Evenkian shamans had virtual contact with Deer-Mother during their shamanic initiation. Deer-Mother virtually ʻswallowed’ the soul of the young shaman and then created a zoomorphic spirit-double of the shaman, her or his spirit-patron.’5

In terms of Christmas traditions, forget Rudolf the reindeer, because the only reindeer to keep their antlers in winter time are, in fact, female.

'In the ancient northern religions it was the female horned reindeer who drew the sleigh of the mother or sun goddess at winter solstice. Unlike the male who sheds his antlers in winter, it is the Deer Mother, who flies through winter's longest darkest night with life-giving light of the sun in her horns. Across the North, since the Neolithic, from the British Isles, Scandinavia, Russia, Siberia, the land bridge of the Bering Strait and into the Americas, the female reindeer was venerated as the 'life-giving mother'. She was the facilitator of fertility, the anima of wild places, forests and mountains, the otherworldly steed of fairies and magical folk.

Her antlers adorned shrines and altars, were buried in ceremonial graves and were worn as shamanic headdresses. Her image was etched in standing stones, woven into ceremonial cloth and clothing, cast in jewellery, painted on drums, and tattooed onto skin!’6

Shamanic Female Deer 🦌 Burials

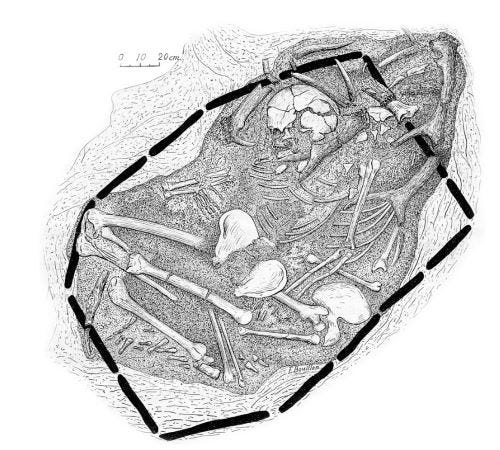

The first example of a shaman, from the Mesolithic, comes from the site of Bad Dürrenburg, Germany, and dates to around 7000 BCE. ‘This individual has been skeletally sexed as female and was buried in a flexed, upright position.’7 She was buried with the remains of many different animals including an antler headdress, which closely resembles the headdresses worn by Evenki Shamans in Siberia.

Interestingly, in Nazi Germany, this burial was thought to be a white man, and interpreted as the ‘original Aryan’. It was later discovered the shaman was, in fact, a female and dark-skinned (like all earliest Europeans leaving Africa), and buried with a child (not her own but related to her).

"Rarely have people been so mistaken about a person as they were about this woman" 8

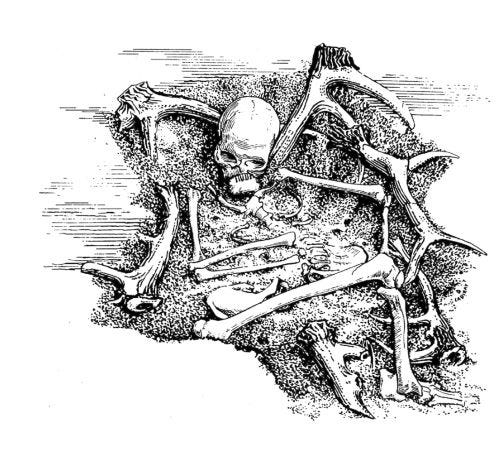

Another, ancient shamanic burial in the Upper Palaeolithic burial is known as the Lady of Saint-Germain-la-Rivière. A young female shaman found buried with a bison skull and reindeer antlers painted with ochre were found near this stone burial. There was rich grave inventory, including lithic tools, shells, weapons, and animal bones, including a fox mandible. Two ‘antler daggers’ were found near the skeleton. The skeleton was also covered with red ochre. The most fascinating feature is the 71 red deer canines, perforated and decorated with parallel notches. They must have been obtained through long-distance trade and represented prestige.9 The stone structure and the inventory of the burial indicate the high status of the buried woman.

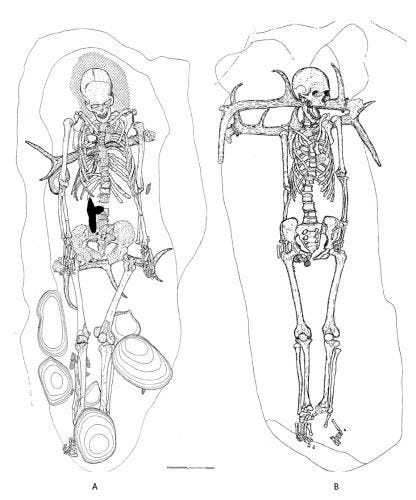

Additional high status female shamanic burials are found in the late Mesolithic at Téviec, France where Tent-like red deer antler structures are associated with two adult females (grave A; Fig. 1) and one adult female with a child.

Then, in the Mesolithic burial complex at Hoëdic, France comprises nine graves, four adults (two males and two females: graves F, H, J, K) were accompanied by shed red deer antlers (Fig. 2; Péquart and Péquart 1954). The two female burials were especially rich.

An undisturbed grave at Vedbæk, Henriksholm-Bøgebakken, Denmark, contained the well-preserved skeleton of a 40- to 50-year-old female (Fig. 3B). There was no ochre in the grave, but a pair of deer antlers lay below the head and shoulders of the deceased.

There was also awoman with a three-year-old child buried in the Vedbæk-Gøngehusvej 7 burial complex in Denmark.

‘The grave was deep, and the sides of the grave, beginning at the top, had been strewn with ochre. There was bird beak near the head of the woman, probably part of a headdress. There were roe deer phalanges on the torso; possibly the woman had been wrapped in a roe deer skin. Both individuals were accompanied by pendants made from animal teeth, bone and stone pendants, flint and bone knives, a bone hairpin and needles, and an abundance of red ochre’10

Finally, looking to a unique site called Star Carr in Yorkshire England dates to around 9000 BCE, reveals the importance of deer headdresses.

‘Although no human remains have been found at the site, it is well known for its ritualized archaeology, including an engraved pendant and, interestingly, an assemblage of antler headdresses. As with the site of Bad Dürrenburg, the headdresses found at Star Carr closely resemble those used by the Evenki people in Siberia. Many of these headdresses or ‘antler frontlets’ have holes drilled through the parietal bone in the skull which would allow them to be worn on the top of the head with a strap.

So far, 24 of these headdresses have been found. This suggests that the site of Star Carr was of great ritualistic importance to the population living in the area during the Mesolithic. An alternative interpretation is that the headdresses were used as a disguise when hunting red deer.’11

Mother Deer Mythology

‘The deer/elk cult is a myth-ritual complex. The object of worship is a sacred deer, incarnated as a female deity known as Deer-Mother, who is a zoomorphic and, later, zooanthropomorphic ancestor.’12

Whether through burial sites, rock paintings, ritual items, oral histories, mythology and folktales, throughout Europe we can trace a great important placed on the deer.

‘There formerly existed in the Highlands of Scotland two cults, probably pre-Celtic, a deer-cult and a deer-goddess cult. The latter cult was administered by women only, and both cults originated during a period when woman was paramount.’13

“The gigantic stature of these Old Women, their love for their deer, the fact that their dealings are almost exclusively with hunters and the fact that each is referred to as a bean-sidhe, or supernatural woman seems sufficient warrant for calling them Deer Goddesses"14

For the Sami people, Beaivi is the name for the Sun Goddess associated with motherhood, the fertility of plants and the reindeer. Beaivi was often shown accompanied by her daughter in an enclosure of reindeer antlers and together they returned green and fertility to the land. The Sami Sun-deity is usually depicted as female, but also sometimes as male. In Sápmi, north of the Polar circle, where the sun does not even reach the horizon in winter, the sun was widely venerated and played a major role in the cultic coherence. On the winter solstice, a white female animal or animals, usually reindeer, were sacrificed in honor of Beivve, to ensure that she returned to the world and put an end to the long winter season. The sacrificed animals' meat would be threaded onto sticks, which were then bent into rings and tied with bright ribbons. This is called the Festival of Beaivi.

Many winter goddesses in northern legends were associated with the solstice. They took to the skies led by flying animals. One tells of the return of Saule, the Lithuanian and Latvian goddess of the sun.

In Latvian folk songs, Saule and her daughter(s) are dressed of shawls woven with gold thread and Saule wears shoes of gold. She is also depicted in a silver, gold or silk costume and wearing a sparkling crown.

She is sometimes portrayed as waking up "red" (sārta) or "in a red tree" during the morning. Saule is also said to own golden tools and garments: slippers, scarf, belt, and a golden boat she uses as her means of transportation. Other accounts ascribe her golden rings, golden ribbons, golden tassels, and even a golden crown.

Saule is also described as being dressed in clothes woven with "threads of red, gold, silver and white". In the Lithuanian tradition, the sun is also described as a "golden wheel" or a "golden circle" that rolls down the mountain at sunset. Also in Latvian riddles and songs, Saule is associated with the color red as if to indicate the "fiery aspect" of the sun: the setting and the rising sun are equated with a rose wreath and a rose in bloom due to their circular shapes.

She flew across the heavens in a sleigh (kamanina) made of fish bones, or “a gleaming copper chariot” pulled by horned reindeer or horses and threw pebbles of amber (symbolizing the sun) into chimneys.

In a Latvian folksong, Saule hangs her sparkling crown on a tree in the evening and enters a golden boat to sail away.

Part 2 of this Series to follow…

Sources:

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0152136

https://brewminate.com/shaman-burials-and-gendered-images-in-prehistoric-europe/

https://gathervictoria.com/2017/12/15/doe-a-deer-a-female-deer-the-spirit-of-mother-christmas/

https://www.thecollector.com/shamans-mesolithic-period/

https://www.marieclaire.com/politics/a34977366/sami-women-reindeer-herders-ancestral-lands/

https://www.dw.com/en/how-nazis-whitewashed-a-prehistoric-shamans-remains/a-64196637

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaivi

Saule:

West 2007, pp. 220–221.

Enthoven, R. E. (1937). "The Latvians in Their Folk Songs". Folklore. 48 (2): 183–186. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1937.9718685. JSTOR 1257244.

Massetti 2019, pp. 232–233.

Motz, Lotte (1997). The Faces of the Goddess. Oxford University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-19-802503-0.

Laurinkienė, Nijolė (2018). "Saulės bei metalų kultas ir mitologizuotoji kalvystė. Metalų laikotarpio idėjų atšvaitai baltų religijoje ir mitologijoje". Būdas (in Lithuanian).

Andrews, Tamra. Dictionary of Nature Myths: Legends of the Earth, Sea, and Sky. Oxford University Press. 1998. p. 169. ISBN 0-19-513677-2

Maria Popova, the Marginalian

Okladnikov 1950, 317; Anisimov 1958, 104

Anisimov 1958, 144

Danielle Prohom Olson, Gather Victoria

Archaeologists Harald Meller and Kai Michel, in their book "Das Rätsel der Schamanin: Eine Reise in unsere Vergangenheit," (German for: "The Riddle of the Shaman: A Journey into Our Past")

Vanhaeren and D’Errico 2005

https://brewminate.com/shaman-burials-and-gendered-images-in-prehistoric-europe/

https://www.thecollector.com/shamans-mesolithic-period/

Anisimov 1958, 104; Simchenko 1976, 270; Popov 1936, 88-89; Potapov 1935, 139; Okladnikov 1950; Jacobson 1993; 2001; Mykhailova 2017a, 57-58

J G McKay