Today, we’re exploring further the possible indigenous and deep feminine roots of Christmas traditions from Santa (or possibly a Goddess) flying in the sky delivering gifts and blessings, to caroling, and the Twelve Days of Christmas from Dec 25th to January 6th (when the spirits roam). We are just exploring clues of more ancient roots as there are no definitive conclusions of where each tradition originated from.

Wishing you a beautiful end of year.

The Wild Hunt

When exploring the roots of Christmas Traditions many point to the Wild Hunt (coined by the Grimm brothers) as the source of a man flying in the sky delivering blessings and presents, but could it also begun as a woman flying through the sky?

The Wild Hunt, or Wotans Wild Hunt, is a survival of Germanic pagan folklore, with similar stories woven across Europe.

In Scandinavia, the Wild Hunt is known as Oskoreia (commonly interpreted as 'The Asgard Ride'), and as Oensjægeren ('Odin's Hunters').1 In the Welsh folklore, Gwyn ap Nudd was depicted as the wild huntsman2, or Cŵn Annwn (hounds of Annwn) is also comparable. In France, the 'Host' was known in Latin sources as Familia Hellequini. In West Slavic Central Europe it is known as divoký hon or štvaní (Czech: 'wild hunt', 'baiting'), Dziki Gon or Dziki Łów (Polish), and Divja Jaga (Slovene: 'the wild hunting party' or 'wild hunt'). To name a few examples.

Grimm believed that this male figure was sometimes replaced by a female counterpart, whom he referred to as Frau Holle or Holda, or Perchta and Berchta.

In his words,

"not only Wuotan and other gods, but heathen goddesses too, may head the furious host: the wild hunter passes into the wood-wife, Wôden into frau Gaude."3

Grimm believed that in pre-Christian Europe, the hunt, led by a god and a goddess, either visited

"the land at some holy tide, bringing welfare and blessing, accepting gifts and offerings of the people" or they alternately float "unseen through the air, perceptible in cloudy shapes, in the roar and howl of the winds, carrying on war, hunting or the game of ninepins, the chief employments of ancient heroes: an array which, less tied down to a definite time, explains more the natural phenomenon."4

He believed that under the influence of Christianisation, the story was converted from being that of a "solemn march of gods" to being "a pack of horrid spectres, dashed with dark and devilish ingredients"

The role of Wotan's Wild Hunt during the Yuletide period has been theorized to have influenced the development of the Dutch Christmas figure Sinterklass, and by extension his American counterpart Santa Claus, in a variety of facets. These include his long white beard and his gray horse for nightly rides.5

So who is Frau Holle, Holda, Perchta and Berchta?

‘In some Scandinavian traditions, Frau Holle is known as the feminine spirit of the woods and plants, and was honored as the sacred embodiment of the earth and land itself. She is associated with many of the evergreen plants that appear during the Yule season, especially mistletoe and holly, and is sometimes seen as an aspect of Frigga, wife of Odin. In this theme, she is associated with fertility and rebirth.

In the Norse Eddas, she is described as Hlodyn, and she gives gifts to women at the time of the Winter Solstice, Yule or Jul. She is sometimes associated with winter snowfall as well. It is said that when Frau Holle shakes out her mattresses, white feathers fall to the earth.’6

Frau Holle's festival is in the middle of winter, the time when humans retreat indoors from the cold. It may be of significance that the Twelve Days of Christmas (Dec 25th to January 5th) were originally the Zwölften ("the Twelve"), which like the same period in the Celtic Calendar to mark the time in-between (to align with gap between moon cycles) during which the dead were thought to roam abroad.7

Holle is the goddess to whom children who died as infants go, and alternatively known as both the Dunkle Großmutter (Dark Grandmother) and the Weisse Frau (White Lady).

She dwells at the bottom of a well, rides a wagon, and first taught the craft of making linen from flax.

As early as the beginning of the 11th century she appears to have been known as the leader of women, and of female nocturnal spirits, which "in common parlance are called Hulden from Holda".

These women would leave their houses in spirit, going "out through closed doors in the silence of the night, leaving their sleeping husbands behind". They would travel vast distances through the sky, to great feasts, or to battles amongst the clouds.

The 9th century Canon Episcopi (medieval law) censures women who claim to have ridden with a "crowd of demons". Burchard's later recension of the same text expands on this in a section titled "De arte magica":

Have you believed there is some female, whom the stupid vulgar call Holda [in some manuscripts strigam Holdam, the witch Holda], who is able to do a certain thing, such that those deceived by the devil affirm themselves by necessity and by command to be required to do, that is, with a crowd of demons transformed into the likeness of women, on fixed nights to be required to ride upon certain beasts, and to themselves be numbered in their company? If you have performed participation in this unbelief, you are required to do penance for one year on designated fast-days.8

Frau Holle and Holda are also thought to be synonymous with Perchta or Berchta.

According to Erika Timm, Perchta or Berchta (“the bright one”) emerged from an amalgamation of Germanic and pre-Germanic, probably Celtic, traditions of the Alpine regions after the Migration period in the Early Middle Ages.9

In the folklore of Bavaria and Austria, Perchta was said to roam the countryside at midwinter, and to enter homes during the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany (especially on the Twelth Jight). She would know whether the children and young servants of the household had behaved well and worked hard all year. If they had, they might find a small silver coin the next day, in a shoe or pail. If they had not, she would slit their bellies open, remove their stomach and guts, and stuff the hole with straw and pebbles.

The word Perchten is plural for Perchta, and this has become the name of her entourage, as well as the name of animal masks worn in parades and festivals in the mountainous regions of Austria. In the 16th century, the Perchten took two forms: Some are beautiful and bright, known as the Schönperchten ("beautiful Perchten"). These come during the Twelve Nights and festivals to "bring luck and wealth to the people." The other form is the Schiachperchten ("ugly Perchten") who have fangs, tusks and horse tails which are used to drive out demons and ghosts. Men dressed as the ugly Perchten during the 16th century and went from house to house driving out bad spirits.

The cult of Perchta, under which followers left food and drink for Fraw Percht and her followers in the hope of receiving wealth and abundance, was condemned in Bavaria in the Thesaurus pauperum (1468) and by Thomas Ebendorfer von Haselbach in De decem praeceptis(1439).

Later canonical and church documents characterized Perchta as synonymous with other leading female spirits: Holda, Diana, Herodias, Richelle and Abundia.

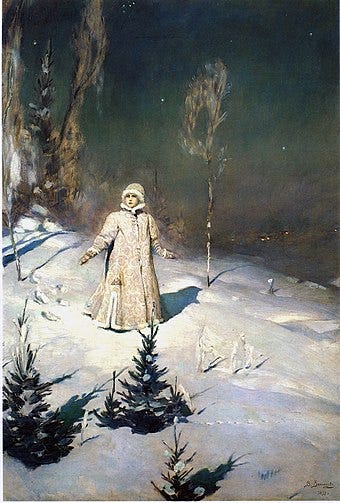

The Snow Maiden

The Twelve Days of Christmas, December 25th to January 6th, was also traditionally celebrated in Ukraine and Russia. Christmas gifts were brought by Ded Moroz or Grandfather Frost, the Ukrainian and Russian counterpart of Saint Nicholas or Father Christmas, albeit a little taller and less stout. Rooted in Slavic folklore, Ded Moroz is accompanied by his beautiful granddaughter, Snegurka the snowmaiden, who rides with him on a sleigh pulled by a trio of horses.

During the early Soviet Period, all religious celebrations were discouraged under the official state policy of atheism. The Bolsheviks argued that Christmas was a pagan sun-worshipping ritual with no basis in scientific fact and denounced the Christmas tree as a bourgeois German import.10

Snegurka The Snow Maiden, is a character found in Russian and Slavic fairy tales. Once a Russian symbol of Christmas time, in the 19th century, in her own right, she later became reinstated (after Soviet collapse) as the granddaughter of Ded Moroz.11

Koliada

Koliada is a Slavic mythological deity and also the traditional Slavic name for the period from Chrstimas to Epiphany or for Slavic Christmas-related rituals, some dating to pre-Christian times. It represents a festival or holiday, celebrated at the end of December to honor the sun during the Northern-hemisphere winter solstice. It also involves groups of singers who visit houses to sing carols and is thought to be where the tradition of caroling comes from.12

The mythological deity is said to represent the newborn winter infant Sun and symbolizing the New Year's cycle. The figure of Koliada is connected with the solar cycle, (the Slavic root *kol- suggests a wheel or circularity) passing through the four seasons and from one substantial condition into another.

In the different Slavic countries at the koliada winter festival people performed rituals with games and songs in honour of the deity - like koleduvane. In some regions of Russia the ritual gifts (usually buns) for the koledari are also called kolyada. In the lands of the Croats a doll, called Koled, symbolized Koliada.13 In the ancient times Slavs used to sacrifice horses, goats, cows, bears or other animals that personify fertility + a clue to deep feminine roots. Koliada is mentioned either as a male or (more commonly) as a female deity in the songs. It is with folk songs that we can trace deep herstorical roots, as a form of oral history.

Back to the Mother Deer 🦌 (see part 1)

Mary B. Kelly's book Goddess Embroideries Of Eastern Europe explores images of the horned deer mother in the sacred textiles of women.

‘The image of the mother goddess Rohanitsa is often shown with antlers and gives birth to deer as well as children. For her feast day in late December (most likely solstice) white iced cookies shaped like deer were given as presents or good luck tokens, and red and white embroidery depicting her image were displayed.’

‘Russian Kozuli are similar cookies baked during winter celebrations, Christmas and New Year. Often called Roe these cookies were originally small three-dimensional figures, most often shaped in the form of reindeer (and birds, fish, bears, flowers, stars and trees - images associated the ancient goddesses of the land). These magical talismans brought wealth, prosperity, good fortune to the family and were also gifted to relatives, friends, neighbors, even the animals and pets! They were displayed in the home as charms to protect from evil spirits and were used for Christmas divination by girls and young men on Epiphany evenings.'14

Read:

Indigenous Roots of Christmas 🎄 Part 1

This week, we’re beginning a deep dive into the shamanic, animistic and deep feminine, or simply indigenous roots of Christmas traditions. This can also be described as pagan Christmas traditions. However, this can get confused within the pagan revival where a lot of traditions and information has been interpreted, guessed, or simply made up.

Kershaw 1997, p. 29.

Greenwood 2008, p. 196.

Grimm 2004b, p. 932.

Grimm 2004b, p. 947.

For example, see McKnight, George Harley (1917). St. Nicholas: His Legend and His Role in the Christmas Celebration and Other Popular Customs, pages 24–26, 138–139. G. P. Putman's sons. & Springwood, Charles Fruehling (2009).

Ginzburg, Carlo (1990). Ecstasies: Deciphering the witches' sabbath. London: Hutchinson Radius.

From the Canon Episcopi, quoted by Ginzburg (1990)

Timm, Erika. 2003. Frau Holle, Frau Percht, und verwandte Gestalten: 160 Jahre nach Grimm aus germanistischer Sicht betrachtet

Sudskov, Dmitry (12 December 2007). "Christmas had to survive dark years of communism to return to Russia". PRAVDA. Retrieved 16 May2019.

"Who were Snegurochka's parents?". postnauka.ru (in Russian). Post-Science. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

Brlic-Mazuranic, Ivana. Croatian Tales of Long Ago. Translated by Fanny S. Copeland. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Co.. 1922. p. 258

Мифологический словарь/Гл.ред. Е.М. Мелетинский - М.:'Советская энциклопедия', 1990 г.- 672 с.

Danielle Prohom Olson, Gather Victoria